|

Elisabeth

HUTCHINSON & Laura GAISFORD

Elizabeth HUTCHINSON,

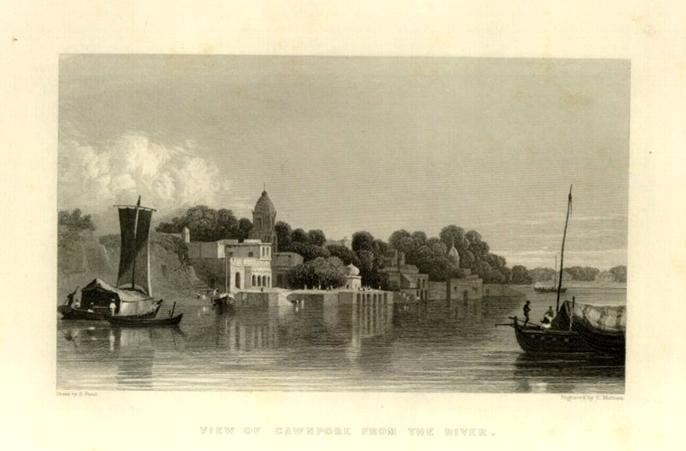

Née à Cawnpore,

Inde, le 11 novembre 1830,

fille de George MONTIER et de Elizabeth HARRINGTON. Elle était veuve du Général

Charles W. Hutchinson et en 1905, elle habitait Craighdu (Ecosse). Elle se

rendait à Dinard où elle avait loué une maison en compagnie de sa fille Laura

qui y résidait.

Born in Cawnpore, India, Nov.11, 1830, she was the daughter of George MONTIER and Elisabeth HARRINGTON. In

1905, widow of the late General Charles W. HUTCHINSON, she was living in

Scotland at Craighdu and was travelling to Dinard where she had rented a house

in company of her daughter Laura who was already living there.

|

|

Laura GAISFORD

|

Laura GAISFORD,

Née en 1866, elle vivait à l’année à Dinard. Elle

avait 3 enfants, deux garçons scolarisés en GB et une fille qui vivait avec

elle mais qui était restée à Dinan chez des amis en attendant son retour. Elle était veuve du Lieutenant Colonel

Gilbert GAISFORD, agent politique de l’Indian Staff Corps qui avait été

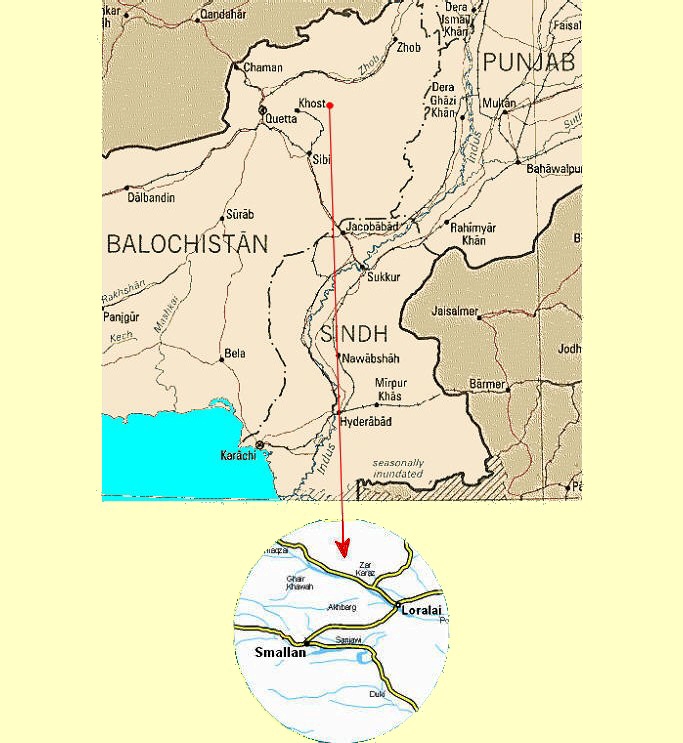

assassiné à Smallan (aujourd’hui au Pakistan) le 15.3.1898 par un fanatique

indien. Les deux garçons allaient l'un et l'autre épouser le métier des armes.

Lionel, le premier était Lieutenant quand il fut tué au combat à Festubert le 23

novembre 1914. Il est inhumé au cimetière militaire de Béthune. Son frère,

Phillip allait devenir Lieutenant Colonel. Il a été annobli en 1942 (Sir

Phillip) lorsqu'il fut fait Chevalier de l'Ordre de l'Empire Indien.

Born in 1866, she was

living in 1905 all year long in Dinard. She had 3 children, 2 boys at school in

GB and a girl who was living with her but who had remained in Dinan at friends

home until her mother’s return. She was widow of Lieut. Colonel Gilbert

CAISFORD, political agent of the Indian Staff Corps who had been murdered at

Smallan (now Pakistan)

by a fanatic indian on 15.3.1898. The two boys were to become Army officers ;

Lionel the first one was killed in action at Festubert on Nov. 23rd, 1914 and

buried at Bethune. His brother Phillip became a Lieut.Colonel and was made

Knight in the Order of Indian Empire.

|

Lieutenant-Colonel Gilbert GAISFORD -

I.S.C.

- assassiné le 15 Mars 1898.

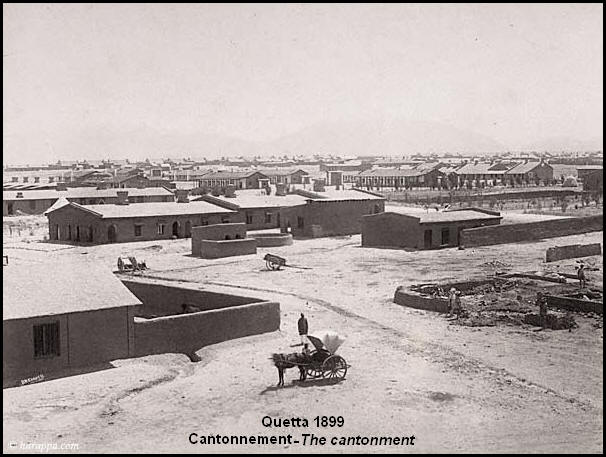

Inhumé à Quetta, sa

tombe porte l'inscription suivante :

« En mémoire

de Gilbert Gaisford, Lieutenant Colonel I.S.C. – Agent politique, Thal Chotiali.

Tué par un fanatique à Smallan le 15 Mars 1898 à l’âge de 48 ans ».

Quetta se trouve à

environ 80km dans l’ouest de Smallan, Pakistan.

Lieutenant-Colonel Gilbert GAISFORD -

I.S.C.

- killed 15th March 1898.

Buried at Quetta,

his grave stone wears the following inscription :

"In loving memory of Gilbert Gaisford. Lieutenant

Colonel ISC. Political Agent, Thal Chotiali. Killed by a fanatic at Smallan 15

March 1898. Aged 48 years."

Quetta is about 80km W of Smallan, Pakistan.

Thal

Chotiali est une vallée proche de Quetta – Thal Chotiali is a valley close

to Quetta

|

|

En juin 1857, Cawnpore et sa région

avaient connu de graves troubles durant ce qui fut appelé « la révolte des

Cipayes » et qui pour les

historiens marque le début de la lutte pour l’indépendance de l’Inde. Cet

épisode dramatique qui se déroula sur les lieux où naquit Mme Hutchinson est

relaté ci-dessous. On peut cependant tenir pour quasi certain qu’elle n’y

vivait plus à cette date.

In June 1857, the Cawnpore area had

known serious troubles during what was to be called “ the sepoy Rebellion”

marking for historians the beginning of India’s independence wars. Those

tragic events that happened at Mrs Hutchinson’s birth place are related below.

However, we can more likely assume that she was no longer living there when the

events occurred.

|

1857

|

Juin

|

|

Lu

|

Ma

|

Me

|

Je

|

Ve

|

Sa

|

Di

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

6

|

7

|

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

13

|

14

|

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

20

|

21

|

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

27

|

28

|

|

29

|

30

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

July

|

|

Mo

|

Tu

|

We

|

Th

|

Fr

|

Sa

|

Su

|

|

|

|

1

|

2

|

3

|

4

|

5

|

|

6

|

7

|

8

|

9

|

10

|

11

|

12

|

|

13

|

14

|

15

|

16

|

17

|

18

|

19

|

|

20

|

21

|

22

|

23

|

24

|

25

|

26

|

|

27

|

28

|

29

|

30

|

31

|

|

|

Cawnpore vue du Gange

|

En Juin, les cipayes de Cawnpore commandés par le

Général Wheeler, se rebellaient et assiégeaient le camp retranché européen.

Wheeler qui était un vétéran et un soldat respecté était marié à une femme

indienne de caste élevée. Il comptait sur son prestige personnel et ses

relations cordiales avec leur chef Nana Sahib pour étouffer la révolte en

conséquence, il avait comparativement pris peu de mesures pour fortifier le

camp et l’approvisionner en vivres et munitions.

Les Britanniques subissaient alors trois

semaines de siège à Cawnpore avec peu d’eau et de nourriture, enregistrant régulièrement

des pertes parmi les hommes, les femmes et les enfants. Le 25 Juin, Nana

Sahib faisait une proposition de reddition en termes plutôt généreux que

Wheeler n’avait d’autre choix qu’accepter. Nana Sahib disait être d’accord

pour garantir un passage en sécurité jusqu’à Allahabad. Mais le 27 Juin,

alors que les Britanniques avaient quitté leur camp fortifié pour rejoindre

les embarcations promises sur le fleuve, une fusillade éclatait. Qui tira le

premier ? La réponse fait toujours débat.

Selon les Indiens, les Anglais avaient déjà pris

place dans les bateaux et le général rebelle Tatya Tope avait levé la main

droite pour donner le signal de départ. C’est à ce moment précis que

quelqu’un dans la foule sonnait du clairon ce qui provoquait un mouvement de

désordre et dans la pagaille qui s’ensuivit, les hommes chargés de manœuvrer

les embarcations sautaient à l’eau. Les soldats et les officiers anglais qui

avaient toujours leurs armes et des munitions, tiraient alors sur eux. Les

rebelles perdant toute patience ouvraient le feu à leur tour sans

discernement. Nana Sahib qui s’était retiré momentanément à Savada Kothi dans

un bungalow proche recevait le message et accourait pour faire cesser le feu.

Les hommes qui restaient furent néanmoins abattus pour éviter toute reprise

des troubles.

|

In June, sepoys under General Wheeler in Cawnpore, rebelled and besieged the European

entrenchment. Wheeler was not only a veteran and respected soldier, but also

married to a high-caste Indian lady. He had relied on his own prestige, and

his cordial relations with the Nana Sahib to thwart rebellion, and took

comparatively few measures to prepare fortifications and lay in supplies and

ammunition.

The British endured three weeks of the Siege of Cawnpore with little water or food, suffering

continuous casualties to men, women and children. On June 25 the Nana Sahib

offered fairly generous surrender terms, and Wheeler had little choice but to

accept. The Nana Sahib agreed to let them have safe passage to Allahabad but on June 27

when the British left their fortified barrack buildings to board the promised

riverboats, firing broke out. Who fired first has remained a matter of

debate.

The Indians claim that the British had already

boarded the boats and Tatya Tope raised his right hand to signal their

departure. That very moment someone from the crowd blew a loud bugle which

created disorder and in the ongoing bewilderment, the boatmen jumped off the

boats. British soldiers and officers still had their arms and ammunition and

they fired shots at these boatmen. The rebels lost all patience and started

shooting indiscriminately. Nana Sahib, who was momen-tarily staying in Savada

Kothi (Bungalow) nearby, got the message and immediately came to stop it. The

remaining men were, however, killed to ensure no further unrest.

The British claim that during the march to the

boats, loyal sepoys were removed by the mutineers and lynched along with any

British officer or soldier that attempted to help them, although these

attacks were ignored in an attempt to reach the boats safely. After firing

began the boats' pilots fled, setting fire to the boats, and the rebellious

sepoys opened fire on the British soldiers and civilians.

|

|

Cawnpore (Kanpur) –

Allahabad |

|

Environ 200 kms par le

fleuve - About 125 miles down the river

|

|

Selon les Britanniques, pendant la marche en

direction des bateaux, des cipayes

restés loyaux étaient extraits de leurs rangs par les mutins et tabassés avec

les officiers et les soldats anglais qui tentaient de s’y opposer. Toutefois,

ces aggressions avaient été ignorées dans le but de rejoindre les bateaux en

sécurité. Après que la fusillade ait débuté, les pilotes des bateaux

s’étaient enfuis en y mettant le feu et les rebelles cipayes avaient tiré sur

les soldats anglais et les civils. L’un des bateaux avec une douzaine de

blessés était parvenu à s’échapper mais s’était échoué et avait alors été

repoussé par les mutins en direction du carnage de Cawnpore. Les femmes qui

étaient à bord avaient été prises en otage tandis que les blessés et des

hommes âgés étaient collés à la hâte dos au mur et fusillés. Seuls 4 hommes

parvenaient à s’échapper vivants de Cawnpore avec un des bateaux : deux

soldats (qui devaient décéder plus tard durant la Rébellion), un

Lieutenant et le Capitaine Mowbray Thomson qui allait ensuite écrire le récit

de son expérience dans « L’histoire de Cawnpore » (Londres, 1859).

Etant donné que les Britanniques assiégés étaient

déjà en train de succomber, il apparaît illogique que Nana Sahib après avoir

garanti un départ en sécurité ait ensuite ordonné le massacre.

|

One boat with over a dozen wounded men initially

escaped, but later grounded, was caught by mutineers and pushed back down the

river towards the carnage at Cawnpore. The

female occupants were removed and taken away as hostages and the men,

including the wounded and elderly, were hastily put against a wall and shot.

Only four men eventually escaped alive from Cawnpore on one of the boats: two

privates (both of whom died later during the Rebellion), a Lieutenant, and

Captain Mowbray Thomson, who wrote a firsthand account of his experiences

entitled “The Story of Cawnpore” (London

1859).

Given that the British were already dying, it defies

logic as to why Nana Sahib would offer a safe passage and then order the

alleged massacre.

The surviving women and children from the massacre

by the river were led to the Bibi-Ghar (the House of the Ladies) in Cawnpore. On July 15, with British forces approaching Cawnpore and some believing that they would not advance

if there were no hostages to save, their murders were ordered. Another motive

for these killings was to ensure that no information was leaked to the

British after the fall of Cawnpore.

|

|

Memorial érigé vers 1860

sur le puits du Bibi-Gahr après que la mutinerie ait été matée.

|

|

A memorial erected circa 1860 at the Bibi Ghar Well

after the Mutiny was crushed. |

|

Les femmes et les enfants qui avaient survécu au

massacre du fleuve furent conduits à la Bibi-Ghar (Maison des Femmes) de Cawnpore. Le

15 Juillet alors que les forces anglaises approchaient de Cawnpore, certains

pensaient qu’elles n’avanceraient pas s’il n’y avait plus d’otages à sauver

et il fut ordonné de les exécuter. Une autre raison pour justifier ces

meurtres était qu’aucune information ne devait parvenir aux Britannqiues après

la chute de Cawnpore. Après que les cipayes aient refusé d’exécuter cet

ordre, quatre bouchers du marché local étaient appelés à Bibi-Gahr où ils

procédaient dit-on au meurtre des otages avec des hachoirs. Les morts et les

mourants avaient ensuite été jetés dans un puits proche.

Ce meurtre des femmes et des enfants s’avéra être

une erreur politique. La population anglaise était atterrée et les défenseurs

des Indiens perdirent tout soutien. Cawnpore allait devenir un cri de guerre

pour les Britannqiues et leurs Alliés pour le reste du conflit. Nana Sahib

pour sa part disparut vers la fin de la Rébellion.

L’interprétation selon laquelle les représailles

anglaises auraient été atroces seulement après les évènements de Cawnpore et

de Bibi-Ghar est délibérée dans certains récits. D’autres récits anglais font

état de mesures punitives discriminatoires prises début Juin, deux semaines

avant les meurtres de Bibi-Ghar, en particulier par le Lieutenant Colonel

James George Neill des Madras Fusiliers (une unité européenne) qu’il

commandait à Allahabad, pendant qu’il faisait mouvement vers Cawnpore. Dans

la ville proche de Fatehpur, un assaillant avait disait-on assassiné la

population anglaise locale. Sur ce prétexte, Neill avait explicitement

ordonné de bouter le feu à tous les villages proches de Grand Truk Road et de

pendre leurs habitants. Les méthodes de Neill étaient « brutales et

horribles » et pouvaient bien avoir incité précédemment les cipayes

indécis et les communautés à la révolte.

Neill fut tué au combat à Lucknow le 26 Septembre

et n’eut jamais à répondre de ces exactions. Certaines sources anglaises

contemporaines firent même de Neill et de ses « braves casquettes

bleues », des héros. Par contraste avec le comportement des hommes de

Neill, le comportement de la plupart des soldats rebelles est à leur crédit.

« Nos croyances ne nous permettent pas de tuer un prisonnier mais

nous pouvons tuer notre ennemi dans la bataille », expliquait l’un

d’entre eux.

Quand le 18 Juillet les Anglais reprirent

Cawnpore, les soldats conduisirent leurs prisonniers cipayes jusqu’au

Bibi-Ghar et les obligèrent à lécher les traces de sang sur les murs et le

sol. Ensuite, ils pendirent ou « désintégrèrent au canon » la

majorité d’entre eux. Bien que selon certains, les cipayes n’aient pas pris

part aux meurtres eux-mêmes, ils n’avaient rien fait pour les empêcher ce qui

fut confirmé par le Capitaine Thompson après que les Anglais eurent quitté

Cawnpore la seconde fois.

|

After the sepoys refused to carry out this order,

four butchers from the local market went into the Bibi-Ghar where they

proceeded to allegedly murder the hostages with cleavers and hatchets. The

dead and the dying were then thrown down nearby a well.

The alleged killing of the women and children proved

to be a mistake. The British public was aghast and the pro-Indian proponents

lost all their support. Cawnpore became a

war cry for the British and their allies for the rest of the conflict. The

Nana Sahib disappeared near the end of the Rebellion.

The misinterpretation that British retaliation was

ghastly only after the events of Cawnpore

and the Bibi Ghar is deliberate in some accounts. Other British accounts

state that indiscriminate punitive measures were taken in early June, two

weeks before the murders at the Bibi-Ghar, specifically by Lieutenant Colonel

James George Smith Neill of the Madras Fusiliers (a European unit),

commanding at Allahabad while moving towards Cawnpore. At the nearby town of Fatehpur, a mob had

allegedly mur-dered the local British population. On this pretext, Neill

explicitly ordered all villages beside the Grand Trunk Road to be burned, and

their inhabitants to be hanged. Neill's methods were "ruthless and

horrible" and may well have induced previously undecided sepoys and

communities to revolt.

Neill was killed in action at Lucknow on September 26 and was never

called to account for his punitive measures, though contemporary British

sources lionised Neill and his "gallant blue caps". By contrast

with the actions of soldiers under Neill, the behaviour of most rebel

soldiers was creditable. "Our creed does not permit us to kill a bound

prisoner", one of the matchlockmen explained, "though we can slay

our enemy in battle."

When on the 18th of July, the British retook Cawnpore, the soldiers took their sepoy prisoners to

the Bibi-Ghar and forced them to lick the bloodstains from the walls and

floor. They then hanged or "blew from the cannon" the majority of

the sepoy prisoners. Although some claimed the sepoys took no actual part in the

killings themselves, they did not act to stop it and this was acknowledged by

Captain Thompson after the British departed Cawnpore

for a second time.

Le drapeau indien de

l’époque

- India’s flag at the time

|

|

Exécution au canon de certains rebelles cipayes

Blowing from the cannon

of some sepoy rebels

|

|

|

|

Mme

Hutchinson et sa fille Laura dont les corps furent retrouvés sur la plage de

Saint Cast sont inhumées au cimetière de Dinard où leur tombe est toujours

parfai-tement entretenue.

Mrs

Hutchinson and her daughter Laura whose bodies were recovered at Saint Cast

are buried in Dinard cemetery where their grave is still beautifully

maintained.

|

|

Lieutenant Lionel (Jack) GAISFORD

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

Fils ainé

|